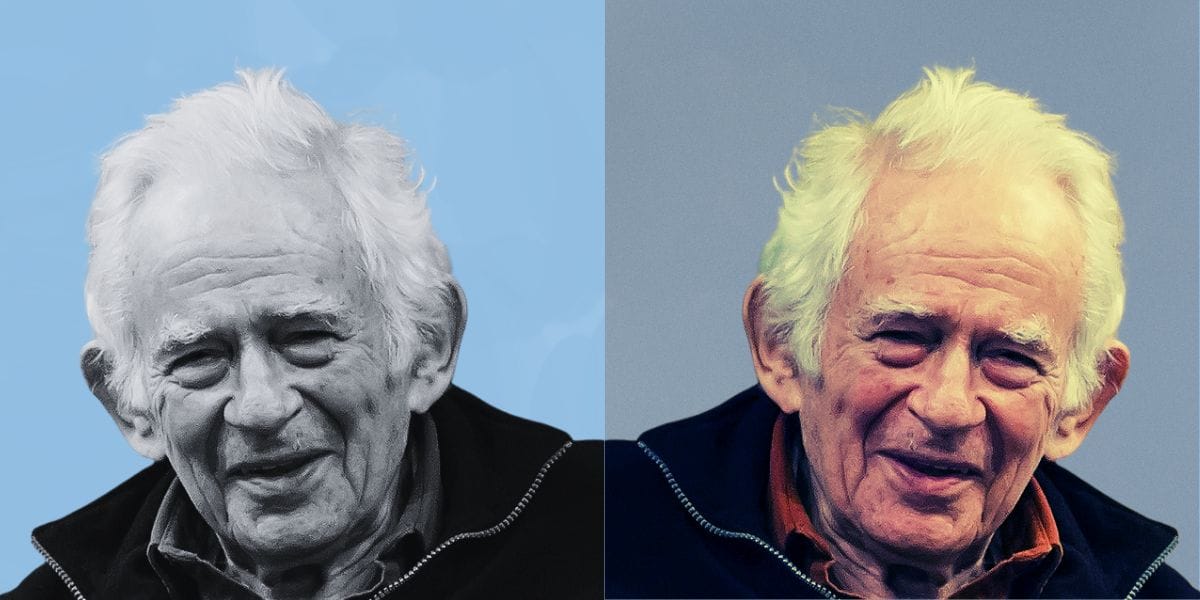

McCarthy and Mailer

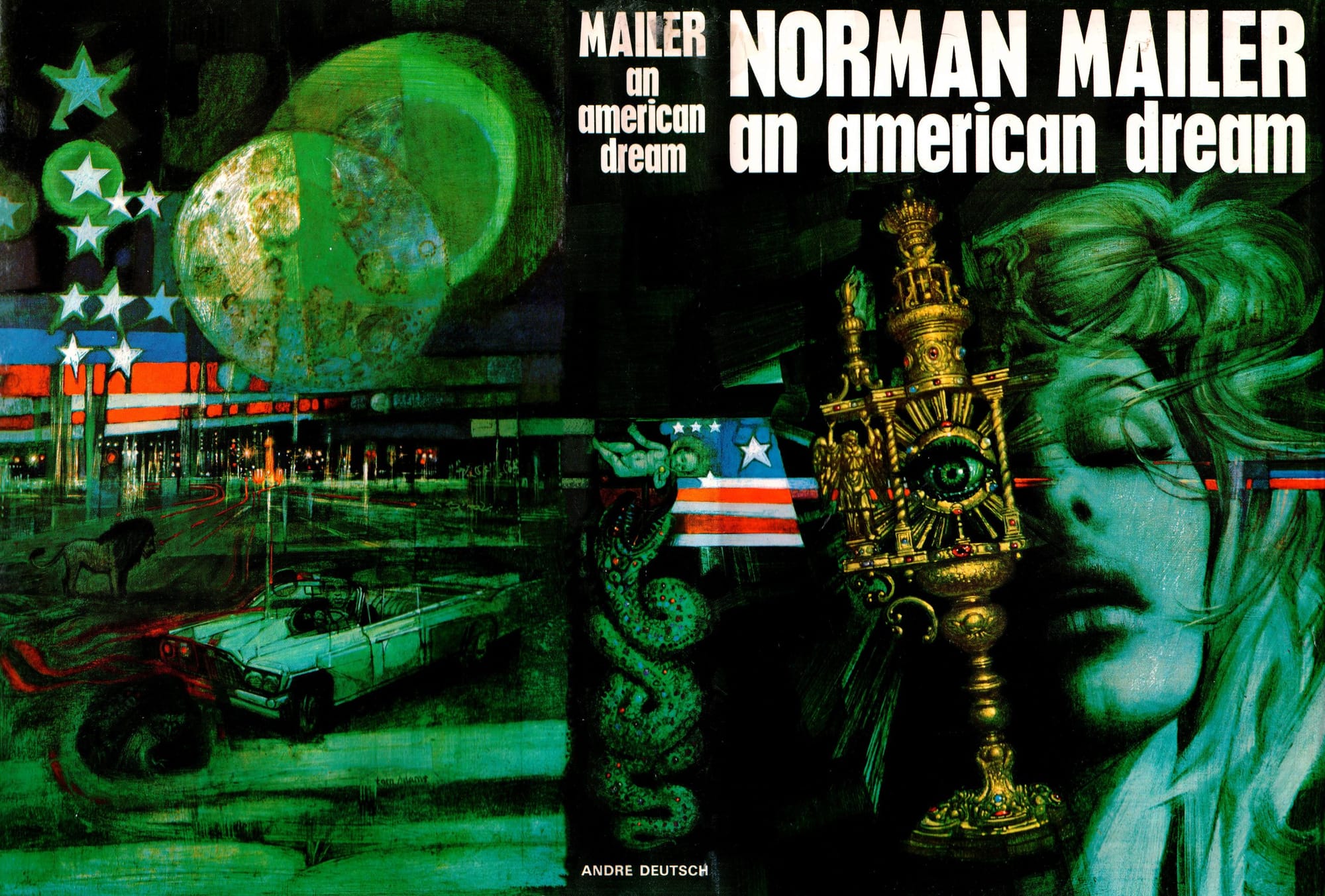

In his Collider article “10 Novels To Read if You Love No Country for Old Men,” Luc Haasbroek recommends Mailer’s An American Dream as a compelling read for fans of Cormac McCarthy's novel. Haasbroek suggests that Mailer's work shares thematic elements with No Country for Old Men, making it a suitable choice for readers interested in exploring similar narratives.

I Can’t Help but Comment...

Luc Haasbroek’s inclusion of An American Dream is an intriguing and, I would argue, largely defensible comparison—though with significant qualifications. While the two novels differ markedly in style, milieu, and philosophical grounding, Haasbroek’s claim holds water when examined through shared thematic and tonal affinities.

Shared Themes: Violence, Fate, and Masculinity

Both An American Dream and No Country for Old Men are meditations on violence and moral decay in postwar America. McCarthy’s novel, suffused with a metaphysical fatalism, pits aging sheriff Ed Tom Bell against a world he no longer understands—a world defined by the psychopathic Anton Chigurh. Similarly, Mailer’s An American Dream explores a descent into violence and the chaotic moral labyrinth of its protagonist, Stephen Rojack, a war hero turned television host who murders his wife and enters a fevered existential spiral.

What unites these works is their engagement with the mythos of American masculinity in crisis. McCarthy’s characters cling to archaic codes of honor; Mailer’s Rojack is a postmodern anti-hero, torn between a search for authenticity and a quest for meaning. Both books dwell in a noirish landscape where morality is ambiguous and the individual is isolated in his battle with internal and external demons.

Mailer’s Existentialism vs. McCarthy’s Fatalism

Where they diverge sharply is in their philosophical underpinnings. Mailer, drawing on Nietzsche, Freud, and Reich, is deeply committed to existential self-creation and psychic warfare. As Barry Leeds notes, An American Dream is “Mailer’s mythic enactment of the psychic struggle for self-definition” (The Enduring Vision of Norman Mailer (2002), 42). Rojack acts not merely out of sociopathy but in a perverse attempt to reclaim his manhood and authenticity in a spiritually degraded society.

McCarthy, on the other hand, leans toward a bleak determinism. Chigurh functions less like a man and more like a symbol of implacable fate or death itself. Sheriff Bell’s lament is not for lost individual agency, but for a world that seems to have slipped beyond moral coherence.

Stylistic Divergences

Stylistically, the contrast is striking. McCarthy’s spare, biblical prose contrasts with Mailer’s flamboyant, psychosexual, and often baroque narration. This makes An American Dream a more fevered, internal experience—almost hallucinatory in tone. As Andrew Gordon emphasizes in An American Dreamer (1980), the novel is “a vision of madness” and psychic fragmentation (14–15).

Do I Agree with Haasbroek?

On balance, yes—with the caveat that Haasbroek’s recommendation is more compelling as a thematic suggestion than a stylistic one. Readers who admire McCarthy for his taut minimalism or his archetypal storytelling may find Mailer’s expressionistic, hypersexualized narrative jarring. But for those intrigued by No Country for Old Men’s exploration of moral anarchy, masculine mythology, and existential dread, An American Dream offers a richly provocative (and more surreal) complement.

Mailer and McCarthy, while aesthetically worlds apart, each chart a vision of American life unmoored from conventional morality—one drenched in myth, brutality, and the dark night of the soul.