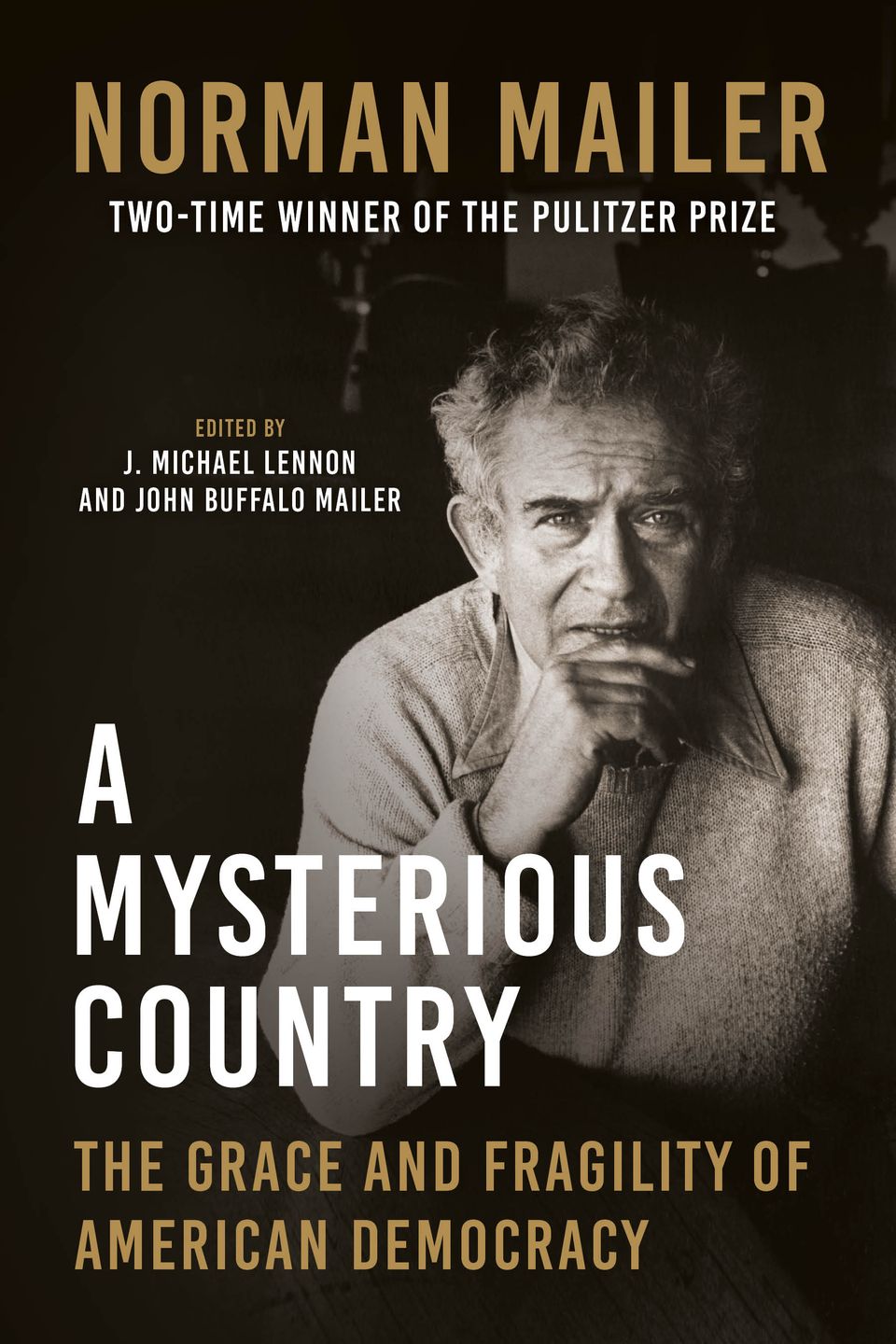

Out Tomorrow: A Mysterious Country

Edited by John Buffalo Mailer and J. Michael Lennon, A Mysterious Country collects Mailer’s commentary on the grace and fragility of democracy, 80 excerpts, 1945-2007, from his books, essays, interviews and letters, many of them uncollected or unpublished. The book is out tomorrow in hardback from Arcade Books; order from Amazon.

Please pass on to anyone worried about the parlous state of our democracy. From the introduction:

Mailer’s early novels are reamed with fears of nascent fascism. In The Naked and the Dead, the crypto-fascist Gen. Cummings tells his Lt. Hearn, his aide, that the principles of fascism are “far sounder than communism if you consider it, for it is grounded in men’s actual natures.” In his next novel, Barbary Shore (1951), Cumming’s predictions of the rightward turn in postwar America are dramatized in the conflict between an FBI agent, Hollingsworth, and McCleod, a former high official of the Communist Party who played a role in the murder of Stalin’s rival Leon Trotsky, but left the party in disgust with Stalin’s brutality. The Red Scare and the blacklist of leftist writers and artists, stoked by the demagoguery of another American reactionary, Senator Joseph McCarthy, is the backdrop to Mailer’s 1955 Hollywood novel, The Deer Park. Mailer’s portrait of Herman Teppis, the right-wing studio head, and the insidious corruptions of Hollywood Babylon, are based on his 18 months spent working as a scriptwriter, along with [Jean] Malaquais, at Warner Brothers.

From the mid-fifties on, Mailer described himself as a “libertarian socialist,” a phrase that captures his desire to join the emerging polarities of his thinking, to build a radical bridge between the Left and the Right, create an alliance that would stand as a bulwark against reactionary nativism. The encroachments of totalitarianism knew no boundaries; the effort to keep democracy alive had to take place in every venue of American life. Consequently, as he stated in a 1955 interview, “politics as politics interests me less today, than politics as part of everything else in life.” On the one hand, he was a proponent of sexual freedom, minority and worker civil rights, and an end to literary censorship, and on the other, he was opposed to corporate greed, environmental destruction, jingoistic patriotism, and the growing and powerful seductions of advertising, all of which he saw as the hydra-heads of totalitarianism.

In 1960, he voted for the first time since 1948, enticed back to the political arena by the candidacy of John F. Kennedy, whose “New Frontier” platform gave promise of a rejuvenation of civic life as the dull fog of conformity during the 1950s began to recede. Kennedy, he believed, could perform the essential duties of governing while also satisfying the nation’s psychological yearnings for greatness, which he called “the dream life of the nation.” Mailer’s deepest aspiration was to create a dialectical relationship not only between the political Left and Right, but also between traditional politics and psychology—more Jungian than Freudian—linking the world of practical affairs with the world of movies, myths, and dreams. His deepest fear was that a polarized nation would devolve into a failed nation.

Member discussion